These excerpts of historic documents are included as background to the 360° vignette in The Black Codes. Rather than depicting specific individuals, the characters in the 360° scene are composites based on people, issues, publications and events relevant to the theme of this module: The contested role of a strong central state before and after the Civil War. The growth of Black Codes in the South shortly after the Civil War made it clear that freedpeople needed the support and protection of the federal government. Although Black Codes established certain rights for freedpeople, in many ways the laws treated them like slaves and tried to reestablish white supremacy. Passage of the first Civil Rights Act in 1866 granted citizenship to Black men, invalidating the Black Codes, and by 1868 most states had repealed them. These primary documents reveal various ways in which white Southerners tried to continue to restrict the rights of freedpeople. The spelling and syntax are historically accurate.

The man in the jail cell in the “Black Codes” scene represents a freedman who has refused to sign a contract with the white landowner whose land he farms. In Florida, control of the labor of Black people was a major goal of the Black Codes, and those who bargained for fair treatment might be considered disrespectful and could be sentenced to jail for vagrancy, as this man has been. The Black Codes were so unfair that they caused the federal government to intervene, as exemplified by the Freedmen’s Bureau agent in our vignette.

The Black Codes in Florida were among the strictest laws in the South, but they were implemented across the former Confederacy. This testimony of a Tennessee freedman tells a story of cruelty and intimidation.

Affidavit of a Tennessee Freedman

[Memphis, Tenn., July 18, 1866 ]

Before me personally appeared the undersigned Archy Paine, who being duly sworn deposes as follows

My name is Archy Paine. I have been living with Andrew Stweart, in Shelby County in the State of Tenn. I made a contract with the said Stweart about the 15th of February last. to worke his farm for half of the Crop. About two months ago, while I was out in the field plowing, He came out there and said that my plow was running too deep. I told him that I guessed not. He said by God I know that it is, And if I told him that it was not again, He would whip me. I told him that I could not help it. At that he got a stick and beat me over the head. he having a knife in his hand at the same time.

Yesterday July 17th I told him that if he did not make his childern stop telling lies on me and my men, I would whip them. At that he had me arrested for threatening to kill his childern. and made me pay sixteen dollars and my wagon for bail. to appear next saturday. July 21′ 1866 for trial. at the Raleigh Court house He told me that I had better leave the state, if I knew what was good for my self. I told him that I would leave his place if he would pay me for what I had done He said he would not do it

his

Archy X Paine

mark

Affidavit of Archy Paine, 18 July 1866, Affidavits & Statements, series 3545, Memphis TN Provost Marshal of Freedmen, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, & Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105, National Archives. Sworn before an officer at the headquarters of the chief superintendent of the Freedmen's Bureau Subdistrict of Memphis.

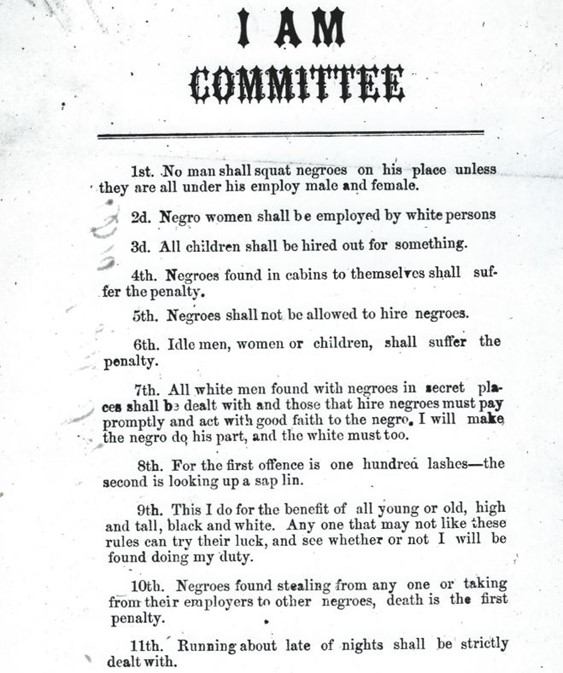

Agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau represented the federal government in the Southern states from 1865 – 1872. In this letter to the Tennessee Assistant Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, an agent describes the terror that a “circular” or leaflet distributed to Black people has inspired. The circular, entitled “I Am Committee,” is below.

Army Officer at Gallatin, Tennessee, to the Headquarters of the Department of the Tennessee, Enclosing an Anonymous Broadside Gallatin Tenn Jan 29. 67.

Col I have the honor to report that I have taken from a house at “Cross Plains” in Robertson Co, 200 copies of the enclosed “circular”: a number of copies had been distributed to certain persons in that neighborhood, and by some of them, read to the colored people living about, at the same time notifying them that they had “been appointed to “see the rules enforced”, and that they intended to do it

Several of the “circulars” have been nailed to the doors of houses located in that vicinity, about Richland, near this place, and near Springfield Tenn,

I am not certain that any of “the penalties” have been inflicted, the negroes are held in such a state of terror that they dare not tell, and the whites, from sympathy with the villains, will not.

I respectfully ask to be informed if the Dept Commander has any instructions to give in this case

I would also ask if Genl Order No 44 A.G.O. July 6. '66 has been superseded by any subsequent order.1 I am sir Very Respy Your Obt Servt

Chas B. Brady

Lt Chas B. Brady to Bvt Lt Col A. L. Hough, 29 Jan. 1867, enclosing “I AM COMMITTEE”

Lt Chas B. Brady to Bvt Lt Col A. L. Hough, 29 Jan. 1867, enclosing “I AM COMMITTEE,” [late 1866 or Jan. 1867], B-10 1867, Letters Received, series 4720, Department of the Tennessee, U.S. Army Continental Commands, Record Group 393 Pt. 1, National Archives. Lieutenant Brady signed as an officer in the 5th Cavalry. In response to his letter, the department commander's chief of staff directed him to arrest “the authors of the Circular, those who posted them, or those who operate under them,” if he could ascertain who they were. General Order 44, he added, had not been superseded.

This letter from freedwoman Levinah Malby to the Freedmen’s Bureau office in Columbia, South Carolina, expresses the desperation of a woman who has not received the share of the crop that was promised to her.

South Carolina Freedwoman to an Unidentified Military Officer

[Orangeburg District, S.C. ] November 18th 1866

Dear General. Sur please do me a peace of kineness if you please Sur. That is for you to see that I shall get my part of the crop that I have laboured for in the year of our freedom that is the yeare of 1865 When peace was Declared. I worked for Mr Middelton Dantzler on the two Chop Road near providence church he and the union troops that came there has promised to give us a Just part of the crop and has not Dun. So as yet they promised to give us a part of the corn peas Rice and potatoes and my Close and So I ours got them as yet he Sed to me that if I got my part I had to go to orange burgh to the yankes and So I ours go them and I taught I would get youre advice on the Subject I am very nead[ey] for it So please General ancer our little note for me if you please by Ben ours very Respec[tfl]

Levinah Malby

Levinah Malby to General, 18 Nov. 1866, enclosed in Bvt Lieut Col H W. Smith to Bt Brig Gen’l J. D. Greene, 21 Nov. 1866, Letters Received, series 3156, Columbia SC Acting Assistant Commissioner, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, & Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105, National Archives. The officer from whom Malby sought assistance was probably General Robert K. Scott, the Freedmen’s Bureau assistant commissioner for South Carolina. In a covering letter of November 21, Scott’s adjutant, acting under instructions from the assistant commissioner, transmitted Malby’s letter to General J. Durell Greene, the bureau’s acting assistant commissioner at Columbia, South Carolina, calling his attention to “the large number of complaints that are coming from Orangeburg District, especially the lower part of the District,” and directing him to “send an efficient officer, and a detachment of men to that district to enforce justice to the Freedpeople.” “The enclosed communication,” he wrote, “is a sample of the complaints, and demands prompt redress. If it becomes necessary to do so, establish a Bureau Court in Orangeburg District, . . . and have all such cases tried before it.”

One of the cruelest of the Black Codes was the forced apprenticeship of children. In this letter, a 12-year-old boy, Carter Holmes, has been apprenticed to a white man named James Suit, and pleads to be reunited with his parents. He gives their names and states that they, “would care for me if they knew where I was.” Apparently they could not be found, as the Freedmen’s Bureau sent Carter to an orphanage.

Maryland Black Apprentice to the Freedmen's Bureau Superintendent at Washington, D.C.

Washington D.C. April 22d 1867

Colonel: I respectfully make the following statement and request that such action may be taken by you in the premises as shall be deemed just.

About three years ago while at Mason's Island I was indentured or bound out by the person in charge there–Dr Nicholls I think–to James Suit living in Prince George County Md about 4 miles from Bladensburgh–who promised me to clothe me, feed and educate me, in compensation for services rendered by me to him–

Mr Suit has been kind to me generally but neither clothed me decently nor sent me to school Once–yes several times I have been whipped by Mr Suit without justification and by Mrs S. also– one time I was struck by her with a shovel–injuring my head very much because I could not fix a pot on a cook stove as she desired.

I have been so tired of not receiving any compensation for my services–no clothing, no chance for school–nothing but whippings that I determined to leave Mr Suit and arrived in this city yesterday–

Please don't let Mr Suit take me back for I have a mother and father (named Sylva and Abraham Holmes) who would care for me if they knew where I was. I think they are in this city. Respectfully Yours

his

Carter X Holmes

mark

Carter Holmes to Lieut. Col. Wm. M. Beebe, 22 Apr. 1867, #1716 1867, Letters Received, series 456, District of Columbia Assistant Commissioner, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, & Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105, National Archives. Witnessed. Beneath Holmes's mark are the words “freed-boy–aged 12 years.” According to an endorsement, the Freedmen's Bureau superintendent sent Holmes to “the Orphan's Home” in Washington.

Many white Southerners who owned land that was worked by enslaved people before the Civil War resented freedpeople making decisions about their own labor. Like the freedman in our “Black Codes” vignette, they could be considered vagrants if they disagreed with the terms of labor dictated by white landowners. In this letter from M.C. Fulton, a Georgia planter, to the Freedmen’s Bureau, Fulton expresses his outrage with freedwomen who have chosen to care for their families rather than work in his fields and suggests that “these idle women” should be considered vagrants.

Georgia Planter to the Freedmen's Bureau Acting Assistant Commissioner for Georgia (excerpt)

Snow Hill near Thomson Georgia April 17th 1866

Dear Sir– Allow me to call your attention to the fact that most of the Freedwomen who have husbands are not at work–never having made any contracts at all– Their husbands are at work–while they are as nearly idle as it is possible for them to be,–pretending to spin–knit or something that really amounts to nothing for their husbands have to buy ther clothing I find from my own hands wishing to buy of me–

Now is a very important time in the crop–& the weather being good & to continue so for the remainder of the year, I think it would be a good thing to put the women to work and all that is necessary to do this in most cases is an order from you directing the agents to require the women to make contracts for the balance of the year– Could not this matter be referred to your agents They are generally very clever men and would do right I would suggest that you give this matter your favorable consideration & if you can do so to use your influence to make these idle women go to work. You would do them & the country a service besides gaining favor & the good opinion of the people generally

M. C. Fulton

Are they not in some sort vagrants–they are living without employment–and mainly without any visible means of support–and if so are they not amenable to vagrant act–? They certainly should be– I may be in error in this matter but I have no patience with idleness or idlers Such people are generally a nuisance–& ought to be reformed if possible or forced to work for a support– Poor white women (and [ri]ch too have [cares?] & business)1 have to work–so should all poor people–or else stealing must be legalized–or tolerated for it is the twin sister of idleness–

M. C. Fulton to Brig Genl Davis Tilson, 17 Apr. 1866, Unregistered Letters Received, series 632, GA Assistant Commissioner, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, & Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105, National Archives. No reply has been found in the acting assistant commissioner's letters-sent volumes.

The jailer in this scene represents a poor white Southerner who has served in the Confederate Army. In contrast to the landowner, most people of his class did not own slaves. Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist renowned for his writings and speeches, was born into slavery. He wrote three autobiographies, and in the third, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, he addressed the plight of people like this jailer, maintaining that slaveholders regarded the “poor laboring white man” as little better than a slave, and encouraged competition between poor whites and enslaved Blacks.

Frederick Douglass on the “craftiness” of slaveholders

The slaveholders, with a craftiness peculiar to themselves, by encouraging the enmity of the poor laboring white man against the blacks, succeeded in making the said white man almost as much a slave as the black slave himself. The difference between the white slave and the black slave was this: the latter belonged to one slaveholder, and the former belonged to the slaveholders collectively. The white slave had taken from him by indirection what the black slave had taken from him directly and without ceremony. Both were plundered, and by the same plunderers. The slave was robbed by his master of all his earnings, above what was required for his bare physical necessities, and the white laboring man was robbed by the slave system, of the just results of his labor, because he was flung into competition with a class of laborers who worked without wages. The slaveholders blinded them to this competition by keeping alive their prejudice against the slaves as men--not against them as slaves. They appealed to their pride, often denouncing emancipation as tending to place the white working man on an equality with negroes, and by this means they succeeded in drawing off the minds of the poor whites from the real fact, that by the rich slave-master, they were already regarded as but a single remove from equality with the slave. The impression was cunningly made that slavery was the only power that could prevent the laboring white man from falling to the level of the slave's poverty and degradation.

From Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape From Bondage, and His Complete History to the Present Time, p. 180