These excerpts of historic documents are included as background to the 360° vignette in The First Vote. Rather than depicting specific individuals, the characters in the 360° scene are composites based on people, issues, publications and events relevant to the theme of this module: Enfranchisement/New Democracy: The role of freedpeople in establishing the right to vote for Blacks. The 360° video is set in a polling place in Virginia during the election of October 22, 1867. The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 required Southern states to write new constitutions that provided for universal manhood suffrage without regard to race. In this election, a long-deferred dream was being realized. 93,145 freedmen voted for the first time, electing 24 African American delegates to the Virginia Constitutional Convention. These primary documents reveal various ways in which white Southerners tried to continue to restrict the rights of freedpeople. The spelling and syntax are historically accurate.

Major William Stone is representative of a white U.S. Army soldier who returned to the South to serve during Reconstruction. Major Stone served in the Nineteenth Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteers and survived four major Civil War battles. In 1866 he arrived in South Carolina as a representative of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Although he didn’t work in a polling place himself, he observed elections taking place after the passage of the Reconstruction Acts in March, 1867, the first in which Black men voted in Southern states . In this excerpt from his journal he describes voter registration in Edgefield, South Carolina. His observations detailing the reluctance of white voters to register and vote in the election are similar to reports of registration efforts across the South.

William Stone, circa 1872

University of South Carolina Press

From Bitter Freedom: William Stone’s Record of Service in the Freedmen’s Bureau, pp. 58-59

Republican clubs were soon formed in which were enrolled nearly all the colored voters…When the registration of voters took place, nearly all who could do so registered, and their number in both Edgefield and Barnwell was considerably larger than that of the whites….While the freedmen were thus active in their efforts to avail themselves of their new rights, the white citizens generally were uncertain as to the course they should pursue. Most who could do so registered but at first were not inclined to vote. Some refused to register on the ground of the illegality of the Reconstruction Acts, and a great many were indifferent to the whole matter. There somehow seemed to prevail a notion that a huge farce was enacting before them, and that were wise who took no part in it. So they held very few meetings and took no pains to secure the votes of the freedmen. Indeed, many men, not in sympathy with the principles of the Republican party, but who were believed to be honorable and just were offered nominations by the freedmen but they refused to accept them.

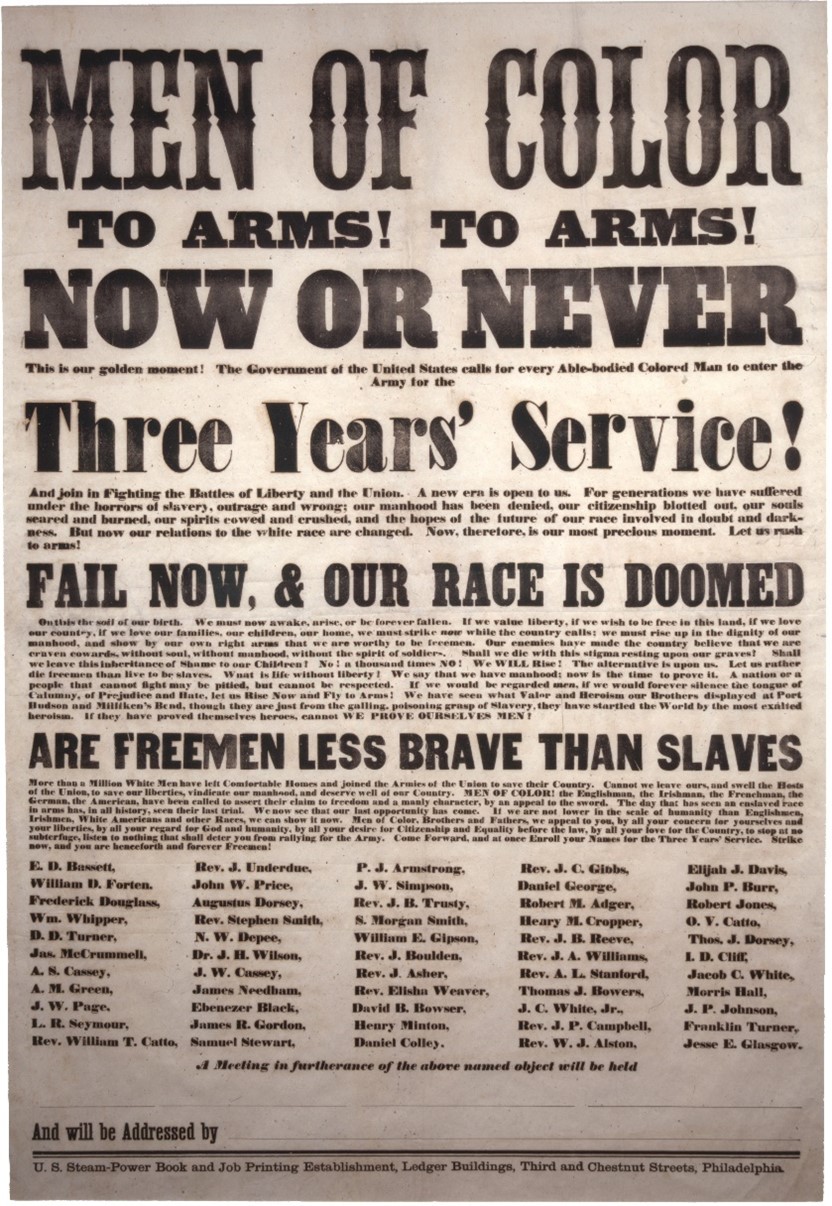

The character of the Black U.S. Army soldier in this scene represents one of the many African American men who served on the side of the Union during the Civil War. At the beginning of the war many Black men wanted to volunteer for the military but a Federal law prohibited Blacks from bearing arms for the U.S. army. After President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, Black leaders, including Frederick Douglass, began to encourage African American men to volunteer (his name is at the bottom of this flyer, third from the top in the first row). Many men answered the call, and in May 1863 the Government established the Bureau of Colored Troops.

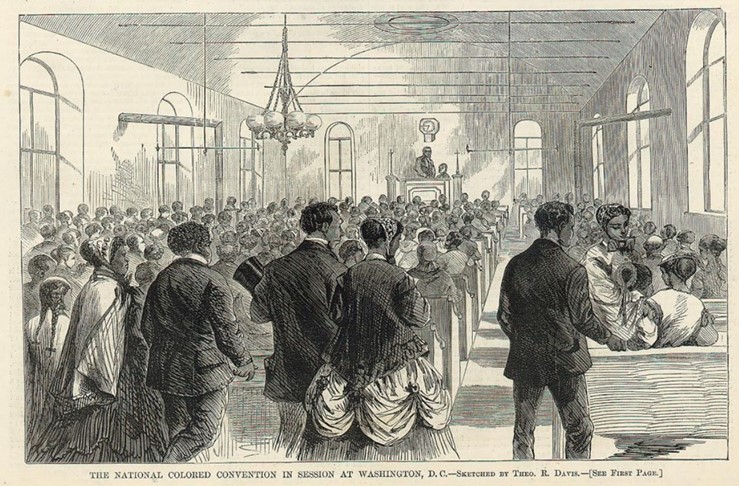

The character of the freedwoman in this scene typifies the efforts of Black women to support their husbands and families during Reconstruction. Although the Fifteenth Amendment did not grant the right to vote to women, Black women were integral to the success of their communities and families, and they participated in conventions that were part of the Colored Conventions Movement. Beginning in 1830, these political conventions were held at the state, regional and national levels and gave Black people an organizational structure for pursuing their rights and freedom. For more on the Colored Conventions, visit https://coloredconventions.org/.

Excerpt from Liberty, and equality before the law. :Proceedings of the Convention of the Colored People of Va., held in the city of Alexandria, Aug. 2, 3, 4, 5, 1865.

We have been forced to silence and inaction; to look on the infernal spectacle of our sons groaning under the lash; our daughters ravisehed; our wives violated, and our firesides desolated, while we ourselves have been led to the shambles, and sold like beasts of the field.

When the nation in her hour of trial called her sable sons to arms, we gladly went and fought her battles, but were denied the pay accorded to others until public opinion demanded it, and even then it was tardily granted.

We have fought and conquered, but have been denied the benefits of victory.

We have fought where victory gave us no glory, and where captivity meant cold blooded murder on the field, and no black man flinched. We are taxed, but denied the right of representation; we are practically debarred the right of trial by jury, and institutions of learning which we help to support are closed against us.

Such being our wrongs, we submit to the American people and to the world the following declaration of rights, asking a calm consideration thereof:

"All men being born free and equal, no man or Government has a right to annul, repeal, or render inoperative, this fundamental principle, except it be for crime; therefore, we ask the immediate repeal of all laws operating against us as a separate class of people.

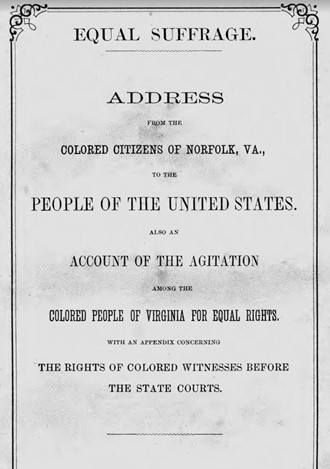

This character represents one of the few African Americans who has already cast a ballot. In 1865, shortly before the end of the Civil War, a group of about a thousand Black men in Norfolk, Virginia formed the Colored Monitor Union Club. Their manifesto, The Equal Suffrage Address, which they distributed nationally, called for “the right of universal suffrage to all loyal men, without distinction of color.” When a local election was held about a month later, on May 25, 1865, members of the club came out to vote in a demonstration of political will. Although most of them were turned back, a few were allowed to vote, in what may be the first instance of African Americans voting in the South.

Excerpt from Equal Suffrage: An Appeal from the Colored Citizens of Norfolk, Va., to the People of the United States Colored Monitor Union Club. June 5, 1865

Fellow Citizens: The undersigned have been appointed a committee, by a public meeting of the colored citizens of Norfolk, held June 5th, 1865, in the Catharine Street Baptist Church, Norfolk, Va., to lay before you a few considerations touching the present position of the colored population of the southern States generally, and with reference to their claim for equal suffrage in particular. We do not come before the people of the United States asking an impossibility; we simply ask that a Christian and enlightened people shall, at once, concede to us the full enjoyment of those privileges of full citizenship, which, not only, are our undoubted right, but are indispensable to that elevation and prosperity of our people, which must be the desire of every patriot. The people of the North, owing to the greater interest excited by the war, have heard little or nothing, for the past four years, of the blasphemous and horrible theories formerly propounded for the defence and glorification of human slavery, in the press, the pulpit and legislatures of the southern States; but, though they may have forgotten them, let them be assured that these doctrines have by no means faded from the minds of the people of the South; they cling to these delusions still, and only hug them the closer for their recent defeat. Worse than all, they have returned to their homes, with all their old pride and contempt for the negro transformed into bitter hate for the new-made freeman, who aspires to the exercise of his new-found rights, and who has been fighting for the suppression of their rebellion.

Equal Suffrage Address from the Colored Citizens of Norfolk, Va., to the People of the United States. Also an Account of the Agitation Among the Colored People of Virginia for Equal Rights. With an Appendix Concerning the Rights of Colored Witnesses Before the State Courts, June 5, 1865. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

From 1936 to 1940 the federal government hired unemployed writers through the Folklore Project of the Federal Writers’ Project, to chronicle the lives of Americans across the country. The following is an excerpt from an interview with Sarah Ann Ross Pringle of McLennan County, Texas, conducted by Effie Cowan. Ms. Pringle expresses views common to former confederates, using the term “carpetbaggers” to describe Northerners and freedmen, and alludes to the formation of the Ku Klux Klan.

Excerpt from interview with Sarah Ann Ross Pringle, conducted by Effie Cowan

When we came to Texas following the close of the war, the state was going / thro' the reconstruction period. The state was under military rule and Pease was Governor. Congress passed a law that every white man in the South must take an oath whether he had held any state or Federal office before the war and if later he had aided the cause of the Confederacy. Those who had done these things were disqualified as voters in the election's. This naturally barred most of the leading white citizens of the state. This gave the negro the right to vote and hold office. So [as?] you know the effect was [to?] [place?] the government in the hand of what we called the “carpetbaggers” [white?] men from the North and the freed negroes.

“I am telling you just what I remember, when we had to go to town during this time we [never?] went without some of our men with us, the negroes were [stationed?] at all the cross roads and bridges when there was any thing of importance taking place. If they spoke or {Begin deleted text}[?]{End deleted text} said insulting things to us we went our way and ignored them, but dared [not?] let our men whip them. Finally it got so bad when E.J. Davis was govorner that the Ku-Klux-Klan was organized. It was told by the carpet baggers that it was to intimidate the negroes and take away their voting privilige.