These excerpts of historic documents are included as background to the 360° vignette in A Seat at the Table. Rather than depicting specific individuals, the characters in the reenactment are composites based on people, issues, publications and events relevant to the theme of African American institution building. The theme emphasizes the role of Black people as active agents in the creation of Reconstruction before and after Emancipation. The documents focus mainly on the institution of the family as foundational to the lives of Black people after freedom. The spelling and syntax are historically accurate.

The grandfather of this family, who represents a newly freed generation of elders, is reading from the Book of Exodus in the Bible. The story of Moses leading the Israelites towards the promised land resonated deeply with enslaved people, but reading scripture aloud could be potentially dangerous if the meaning of the scripture was meant to stand for escape from enslavement. Post-emancipation, freedmen could publicly embrace the emancipatory themes of Exodus.

Exodus 14:13-31

The Bible - New King James Version

And Moses said to the people, “Do not be afraid. Stand still, and see the salvation of the Lord, which He will accomplish for you today. For the Egyptians whom you see today, you shall see again no more forever. The Lord will fight for you, and you shall hold your peace.”

And the Lord said to Moses, “Why do you cry to Me? Tell the children of Israel to go forward. But lift up your rod, and stretch out your hand over the sea and divide it. And the children of Israel shall go on dry ground through the midst of the sea. And I indeed will harden the hearts of the Egyptians, and they shall follow them. So I will gain honor over Pharaoh and over all his army, his chariots, and his horsemen. Then the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord, when I have gained honor for Myself over Pharaoh, his chariots, and his horsemen.”

And the Angel of God, who went before the camp of Israel, moved and went behind them; and the pillar of cloud went from before them and stood behind them. So it came between the camp of the Egyptians and the camp of Israel. Thus it was a cloud and darkness to the one, and it gave light by night to the other, so that the one did not come near the other all that night.

Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea; and the Lord caused the sea to go back by a strong east wind all that night, and made the sea into dry land, and the waters were divided. So the children of Israel went into the midst of the sea on the dry ground, and the waters were a wall to them on their right hand and on their left. And the Egyptians pursued and went after them into the midst of the sea, all Pharaoh’s horses, his chariots, and his horsemen.

Now it came to pass, in the morning watch, that the Lord looked down upon the army of the Egyptians through the pillar of fire and cloud, and He troubled the army of the Egyptians. And He took off their chariot wheels, so that they drove them with difficulty; and the Egyptians said, “Let us flee from the face of Israel, for the Lord fights for them against the Egyptians.”

Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, that the waters may come back upon the Egyptians, on their chariots, and on their horsemen.” And Moses stretched out his hand over the sea; and when the morning appeared, the sea returned to its full depth, while the Egyptians were fleeing into it. So the Lord overthrew the Egyptians in the midst of the sea. Then the waters returned and covered the chariots, the horsemen, and all the army of Pharaoh that came into the sea after them. Not so much as one of them remained. But the children of Israel had walked on dry land in the midst of the sea, and the waters were a wall to them on their right hand and on their left.

So the Lord saved Israel that day out of the hand of the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore. Thus Israel saw the great work which the Lord had done in Egypt; so the people feared the Lord, and believed the Lord and His servant Moses.

The character of the Mother in A Seat at the Table represents a freedwoman who is finally able to marry and care for her own family. Marriage was forbidden to most enslaved people although they deeply desired it, as the chaplain of a black regiment in Arkansas notes in this letter. He emphasizes the importance of marriage to freedpeople, who, he says, regarded their wartime emancipation as a step toward “an honorable Citizenship.”

Chaplain of an Arkansas Black Regiment to the Adjutant General of the Army, February 28, 1865

Little Rock Ark Feb 28th 1865

Weddings, just now, are very popular, and abundant among the Colored People. They have just learned, of the Special Order No' 15. of Gen Thomas1 by which, they may not only be lawfully married, but have their Marriage Certificates, Recorded; in a book furnished by the Government. This is most desirable; and the order, was very opportune; as these people were constantly loosing their certificates. Those who were captured from the “Chepewa”; at Ivy's Ford, on the 17th of January, by Col Brooks, had their Marriage Certificates, taken from them; and destroyed; and then were roundly cursed, for having such papers in their posession. I have married, during the month, at this Post; Twenty five couples; mostly, those, who have families; & have been living together for years. I try to dissuade single men, who are soldiers, from marrying, till their time of enlistment is out: as that course seems to me, to be most judicious.

The Colord People here, generally consider, this war not only; their exodus, from bondage; but the road, to Responsibility; Competency; and an honorable Citizenship– God grant that their hopes and expectations may be fully realized. Most Respectfully

A. B. Randall

Chaplain A. B. Randall to Brig. Gen. L. Thomas, 28 Feb. 1865, R-189 1865, Letters Received, series 12, Adjutant General's Office, Record Group 94, National Archives

***

As represented by the Mother in A Seat at the Table, many freedwomen chose not to work for white employers, preferring to care for their children and manage their own households, when the circumstances of their families allowed. In this letter to the Freedmen’s Bureau, a planter in Georgia denounces the fact that freedwomen are not signing labor contracts with white landowners, calling them “bad examples” and “mischief makers.”

Letter from M.C. Fulton to Brig Genl Davis Tilson, the Freedmen's Bureau Acting Assistant Commissioner for Georgia

Snow Hill near Thomson Georgia April 17th 1866

Dear Sir– Allow me to call your attention to the fact that most of the Freedwomen who have husbands are not at work–never having made any contracts at all– Their husbands are at work–while they are as nearly idle as it is possible for them to be,–pretending to spin–knit or something that really amounts to nothing for their husbands have to buy ther clothing I find from my own hands wishing to buy of me–

Now these women have always been used to working out–& it would be far better for them to go to work for reasonable wages & their rations–both in regard to health & in furtherance of their family wellbeing– Say their husbands get–10 to 12– or 13$ per month and out of that–feed their wives and from 1 to 3 or 4 children–& clothe the family– It is impossible for one man to do this & maintain his wife in idleness without stealing more or less of their support–whereas if their wives (where they are able) were at work for rations & fair wages–which they can all get, the family could live in some comfort & more happily–besides their labor is a very important percent of the entire labor of the South–& if not made avaible, must affect to some extent–the present crop– Now is a very important time in the crop–& the weather being good & to continue so for the remainder of the year, I think it would be a good thing to put the women to work and all that is necessary to do this in most cases is an order from you directing the agents to require the women to make contracts for the balance of the year– I have several that are working well–while others and generally younger ones who have husbands & from 1 to 3 or 4 children are idle–indeed refuse to work & say their husbands must support them. Now & then there is a woman who is not able to work in the field–or who has 3 or 4 children at work & can afford to live on her childrens labobor–with that of her husband– Even in such a case it would be better she should be at work– Generally however most of them should be in the field– Could not this matter be referred to your agents They are generally very clever men and would do right I would suggest that you give this matter your favorable consideration & if you can do so to use your influence to make these idle women go to work. You would do them & the country a service besides gaining favor & the good opinion of the people generally

I beg you will not consider this matter lightly for it is a very great evil & one that the Bureau ought to correct= if they wish the Freedmen & women to do well– I have 4 or 5 good women hands now idle that ought to be at work becase their families cannot really be supported honestly without it This should not be so–& you will readily see how important it is to change it at once– I am very respectfully Your obt servant

M. C. Fulton

I am very willing to carry my idle women to the Bureau agency & give them such wages as the Agent may think, fair–& I will further garanty that they shall be treated kindly & not over worked– I find a general complaint on this subject every where I go–and I have seen it myself and experienced its bad effects among my own hands– These idle women are bad examples to those at work & they are often mischief makers–having no employment their brain becomes more or less the Devil's work shop as is always the case with idle people–black or white & quarrels & Musses among the colored people generally can be traced to these idle folks that are neither serving God– Man or their country–

Are they not in some sort vagrants–they are living without employment–and mainly without any visible means of support–and if so are they not amenable to vagrant act–? They certainly should be– I may be in error in this matter but I have no patience with idleness or idlers Such people are generally a nuisance–& ought to be reformed if possible or forced to work for a support– Poor white women (and [ri]ch too have [cares?] & business)1 have to work–so should all poor people–or else stealing must be legalized–or tolerated for it is the twin sister of idleness–

M. C. Fulton to Brig Genl Davis Tilson, 17 Apr. 1866, Unregistered Letters Received, series 632, GA Assistant Commissioner, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, & Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105, National Archives. No reply has been found in the acting assistant commissioner's letters-sent volumes.

***

The Mother in A Seat at the Table works to make life better for needy members of her community. Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in North Carolina in 1813. Her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, recounted the years-long abuse she suffered at the hands of her master. Published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent, it became the most widely-read antebellum female slave narrative. In 1865 she and her daughter went to Savannah, Georgia, to assist in relief work for freedpeople. This letter is an appeal for funds for the Savannah Freedmen’s Orphan Asylum.

Letter from Harriet Jacobs to the government of the City of Savannah. Published in the Anti-Slavery Reporter, March 2, 1868, pp. 57-58.

We have much pleasure in publishing the following Appeal. It is made by a well-known victim of Slavery, Linda Brent, now Harriet Jacob[s], whose narrative, entitled "Linda," every one should read. We hope her appeal will be met with a generous response.

AN APPEAL.

My object in visiting England is to solicit aid in the erection of an Orphan Asylum in connection with a home for the destitute among the aged freedmen of Savannah, Georgia. There are many thousand orphans in the southern states. In a few of the states homes have been established through the benevolence of Northern friends; in others, no provision has been made except through the Freedmen's Bureau, which provides that the orphan be apprenticed till of age. It not unfrequently happens that the apprenticeship is to the former owner. As the spirit of Slavery is not exorcised yet, the child, in many instances, is cruelly treated. It is our earnest desire to do something for this class of children; to give them a shelter surrounded by some home influences, and instruction that shall fit them for usefulness, and, when apprenticed, the right of an oversight. I know of the degradation of Slavery—the blight it leaves; and, thus knowing, feel how strong the necessity is of throwing around the young, who, through God's mercy, have come out of it, the most salutary influences.

The aged freedmen have likewise a claim upon us. Many of them are worn out with field-labour. Some served faithfully as domestic slaves, nursing their masters and masters' children. Infirm, penniless, homeless, they wander about dependent on charity for bread and shelter. Many of them suffer and die from want. Freedom is a priceless boon, but its value is enhanced when accompanied with some of life's comforts. The old freed man and the old freed woman have obtained their's after a long weary march through a desolate way. If some peace and light can be shed on the steps so near the grave, it were but human kindness and Christian love.

I was sent as an agent to Savannah in 1865 by the Friends of New-York city. I there found that a number of coloured persons had organized a Society for the relief of freed orphans and aged freedmen. Their object was to found an asylum, and take the destitute of that class under their care. They asked my co-operation. I promised my assistance, with the understanding that they should raise among themselves the money to purchase the land. They are now working for that purpose. Their plan is to make the institution wholly, or in part, self-sustaining. It is proposed to cultivate the land (about fifteen acres) in vegetables and fruit. The institution will thereby be supplied, while a large surplus will remain for market sale. Poultry will also be raised for the market. This arrangement will afford a pleasant occupation to many of the old people, and a useful one to the older children out of school hours. I am deeply sensible of the interest taken and the aid rendered by the friends of Great Britain since the emancipation of Slavery. It is a noble evidence of their joy at the downfall of American Slavery and the advancement of human rights. I shall be grateful to any who shall respond to my efforts for the object in view. Every mite will tell in the balance.

LINDA JACOBS.

"Contributions can be sent to

"STAFFORD ALLEN, ESQ., Honorary Secretary, 17, Church Street.

ROBERT ALSOP, ESQ., 36 Park Road, Stoke Newington, N.

MRS. PETER TAYLOR, Aubrey House, Notting Hill, W."

"Anti Slavery Reporter," 2 March 1868, in http://www.yale.edu/glc/harriet/14.htm, ed. http://www.yale.edu/glc/harriet/14.htm: (http://www.yale.edu/glc/harriet/14.htm: http://www.yale.edu/glc/harriet/14.htm, 1868), 1

The father in the 360° vignette in A Seat at the Table is representative of a Black man who was never enslaved, and lived in Savannah as a free person of color before Emancipation. He might be descended from enslaved people who were emancipated by their enslavers through a process called manumission, or his ancestors might have emigrated from a country such as Haiti where slaves had been freed. In 1860, the year Abraham Lincoln was first elected, there were over 250,000 free Blacks living in the South, and about 705 in Savannah. Some of them, although not the majority, did own their own businesses, and a very few even owned slaves themselves.

Yet, even for free people of color life in the antebellum South was often difficult. They could not travel freely, or organize meetings, churches, schools or fraternal organizations, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 led to free blacks being captured and sold into slavery. But both free and fugitive Blacks fought back. For many decades before and after the Civil War, African Americans organized against injustice. At more than 200 local and national meetings known as “Colored Conventions,” Black men and women came together in a campaign for civil and human rights. Infuriated by the Fugitive Slave Act, African Americans organized a convention in Rochester, New York in 1853. The Proceedings of the Convention were published at the office of Frederick Douglass’ newspaper. We have reprinted the opening of the Proceedings here.

Proceedings of the Colored national convention, held in Rochester, July 6th, 7th, and 8th, 1853.

FELLOW CITIZENS:—In the exercise of a liberty which, we hope, you will not deem unwarrantable, and which is given us, in virtue of our connection and identity with you, the undersigned do hereby, most earnestly and affectionately, invite you, by your appropriate and chosen representatives, to assemble at ROCHESTER, N. Y., on the 6th of July, 1853 under the form and title of a National Convention of the free people of color of the United States.

After due thought and reflection upon the subject, in which has entered a profound desire to serve a common cause, we have arrived at the conclusion, that the time has now fully come when the free colored people from all parts of the United States, should meet together, to confer and deliberate upon their present condition, and upon principles and measures important to their welfare, progress and general improvement.

The aspects of our cause, whether viewed as being hostile or friendly, are alike full of argument in favor of such a Convention. Both reason and feeling have assigned to us a place in the conflict now going on in our land between liberty and equality on the one hand, and slavery and caste on the other-a place which we cannot fail to occupy without branding ourselves as unworthy of our natural post, and recreant to the cause we profess to love.—Under the whole heavens, there is not to be found a people which can show better cause for assembling in such a Convention than we.

Our fellow-countrymen now in chains, to whom we are united in a common destiny demand it; and a wise solicitude for our own honor, and that of our children, impels us to this course of action. We have gross and flagrant wrongs against which, if we are men of spirit we are bound to protest. We have high and holy rights, which every instinct of human nature and every sentiment of manly virtue bid us to preserve and protect to the full extent of our ability. We have opportunities to improve—difficulties peculiar to our condition to meet-mistakes and errors of our own to correct-and therefore we need the accumulated knowledge, the united character, and the combined wisdom of our people to make us (under God) sufficient for these things.—The Fugitive Slave Act, the most cruel, unconstitutional and scandalous outrage of modern times—the proscriptive legislation of several States with a view to drive our people from their borders—the exclusion of our children from schools supported by our money—the prohibition of the exercise of the franchise--the exclusion of colored citizens from the jury box--the social barriers erected against our learning trades--the wily and vigorous efforts of the American Colonization Society to employ the arm of government to expel us from our native land--and withal the propitious awakening to the fact of our condition at home and abroad, which has followed the publication of "Uncle Toms Cabin”—call trumpet-tongued for our union, cooperation and action in the premises.

https://www.loc.gov/item/34008448/. Comprehensive information about the Colored Conventions may be found at https://coloredconventions.org/

***

The Father and Pastor in A Seat at the Table represent delegates to the Georgia Constitutional Convention of 1867-68. Here we have reproduced the first few paragraphs of the address to the delegates by Foster Blodgett, the temporary Chairman of the Convention. As he declares that, “A new era has dawned upon the country,” his words reflect the hopeful mood of early Reconstruction.

Journal of the Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the People of Georgia (pp. 10-11)

Atlanta, Ga., Tuesday, Dec. 10, 1867.

The Convention met at 12 o’clock m., pursuant to adjournment.

Mr. Dunning having called the Convention to order, and having announced the presence of Hon. Foster Blodgett, who had on yesterday been elected temporary Chairman of the Convention, then requested Mr. Blodgett to take the Chair.

Mr. Blodgett took the Chair and Addressed the Convention as follows:

Gentlemen of the Convention:

I am profoundly sensible of the honor conferred on me, in being chosen to preside temporarily over your body at this conjuncture of public affairs.

A new era has dawned upon the country. This great Republic has risen to the full grandeur of its position, and promises to fulfill its glorious destiny. The principles of the Declaration of Independence have, at length, been vindicated; no longer are they obscured in one half of the Union, by the existence of an institution which was a reproach alike to freedom and to civilization. It is now recognized as a great practical as well as theoretical truth, throughout the wide extent of our country, that “all men are created equal – that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights – that among them are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The morning sun, as it rises in the east, gilds the flag of Freedom; and as it descends beneath the waves of the Pacific, it sheds its splendor upon shores where institutions are seated that promise to spread priceless blessings of regulated liberty over the distant nations that have so long dwelt apart from modern civilization.

It is to be regretted that so many of our countrymen, who have grown up under a system which subjected a part of our people to hard and degrading bondage, are slow to comprehend and to acknowledge this great fact. They cling to the ruins of a structure that now belongs to the past. They are under the dominion of ideas that no longer are represented in this country; ideas that are fast disappearing from the civilized world. The great struggle through which the country has just passed was the natural, and may be the necessary result of the advance of the Republic in the career of civilization. It was simply impossible much longer to resist the pressure of the public sentiment of the world against the domestic institution of the Southern States of the American Union. Those who controlled affairs at the South precipitated the result by a vain effort to wrest these plantation States from the Union – an effort that involved in its failure the complete overthrow of that monstrous system which held millions of human beings in a bondage that it required a national convulsion to destroy.

To-day, the Republic is free! This Convention is a splendid exemplification of the fact. Gentlemen, I tender you my congratulations. The whole civilized world greets you to-day, assembled as the representatives of the free State of Georgia.

The entire Journal of the Proceedings of the convention can be accessed at https://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/georgiabooks/pdfs/gb0086.pdf

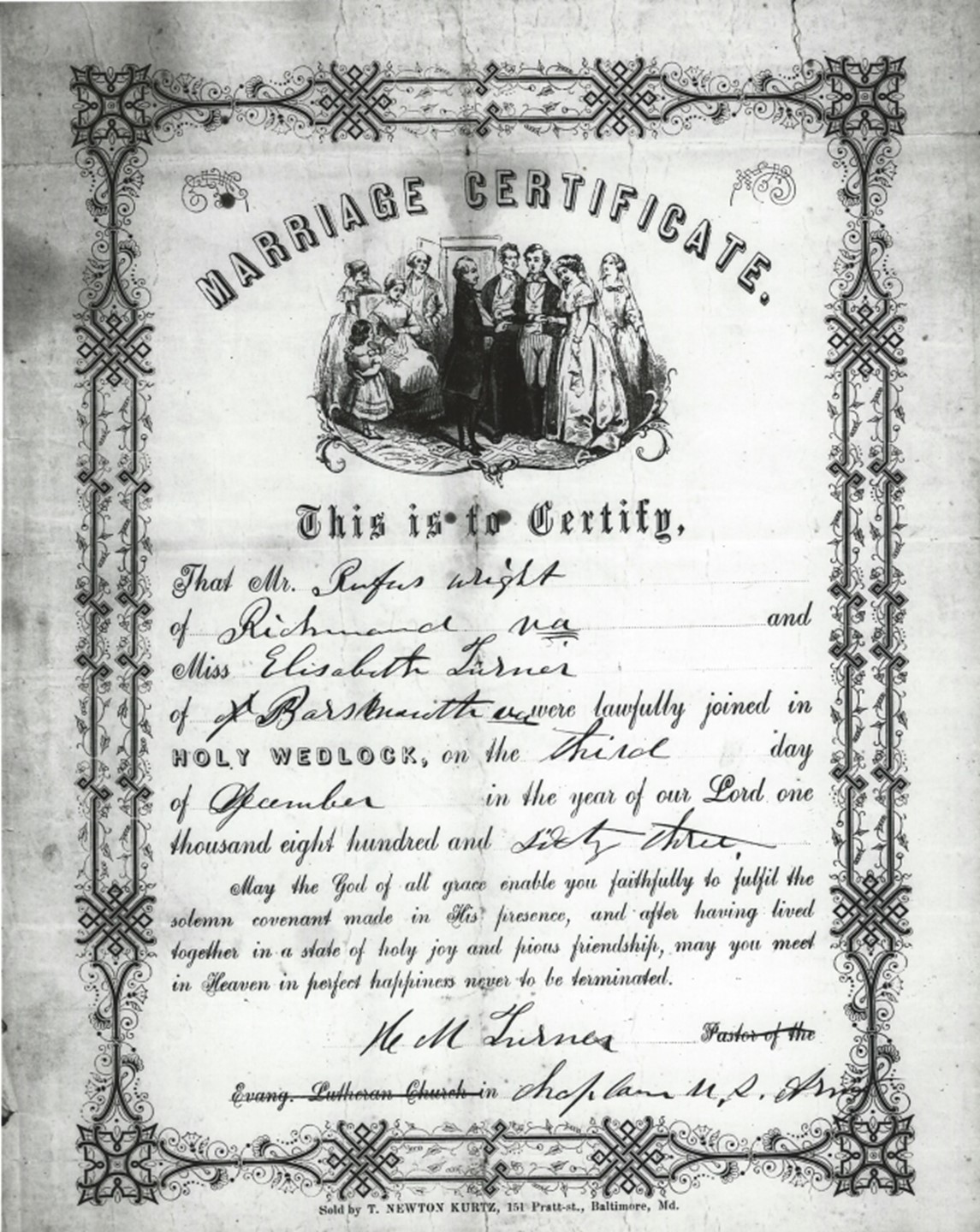

The figure of the Pastor in A Seat at the Table represents the tradition of Black religious leaders who have also served the community politically. Henry McNeal Turner was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, who helped to found the Republican Party of Georgia. This is the 1863 wedding certificate of the marriage between two former slaves: Rufus Wright, a Black soldier who served in the Union Army, and Elisabeth Turner. They were married by Bishop Turner, who was chaplain of Wright’s regiment at the time.

Marriage Certificate of a Black Soldier and His Wife, December 3, 1863

Marriage certificate, 3 Dec. 1863, filed with affidavit of Elisabeth Wright, 21 Aug. 1865, Letters & Orders Received, series 4180, Norfolk VA Assistant Subassistant Commissioner, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, & Abandoned Lands, Record Group 105, National Archives.

***

A.M.E. Bishop Henry McNeal Turner was elected to the Georgia Legislature in 1868. In 1875 Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, prohibiting racial discrimination in transportation and accommodations. In 1883 the Supreme Court declared the Civil Rights Act unconstitutional, and in 1893 Turner published an objection to the ruling that included the full text of the Court’s decision, as well as speeches by Frederick Douglass and others. The ruling against the Act remained in place until the Supreme Court upheld the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The excerpt below is the introduction to Turner’s publication.

THE BARBAROUS DECISION

OF THE

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

DECLARING THE

Civil Rights Act Unconstitutional

AND

DISROBING THE COLORED RACE OF ALL CIVIL PROTECTION.

THE MOST CRUEL AND INHUMAN VERDICT AGAINST A

LOYAL PEOPLE IN THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD.

ALSO

THE POWERFUL SPEECHES

OF

HON. FREDERICK DOUGLASS

AND

COL. ROBERT G. INGERSOLL, JURIST AND FAMOUS ORATOR.

ATLANTA, GA.

COMPILED AND PUBLISHED

BY

BISHOP H. M. TURNER, D. D., LL. D.

1893.

The reason I have gone to the United States Supreme Court library at Washington, D. C., and procured a true and correct copy of the revolting decision, which declared the Civil Rights bill unconstitutional, and entails upon the colored people of the United States every species of indignities known to proscription, persecution and even death itself, and will culminate in their leaving the United States or occupying the status of free slaves, until extermination follows, is because the great mass of our people in this country, including black and white, appear to be so profoundly ignorant of the cruel, disgraceful and inhuman condition of things affecting the colored race, and sustaining the brutal laws, which are degrading and goring their very lives out; I have met hundreds of persons, who, in their stupid ignorance, have attempted to justify the action of the Supreme Court in fettering the arms of justice and disgracing the nation by transforming it into a savage country. The world has never witnessed such barbarous laws entailed upon a free people as have grown out of the decision of the United States Supreme Court, issued October 15, 1883. For that decision alone authorized and now sustains all the unjust discriminations, proscriptions and robberies perpetrated by public carriers upon millions of the nation's most loyal defenders. It fathers all the "Jim-Crow cars" into which colored people are huddled and compelled to pay as much as the whites, who are given the finest accommodations. It has made the ballot of the black man a parody, his citizenship a nullity and his freedom a burlesque. It has ingendered the bitterest feeling between the whites and blacks, and resulted in the deaths of thousands, who would have been living and enjoying life today. And as long as the accompanying decision remains the verdict of the nation, it can never be accepted as a civil, much less a Christian, country.

The colored man or woman who can find contentment, menaced and shackled by such flagrant and stalking injustice as the Supreme Court has inflicted upon them, must be devoid of all manliness and those self-protecting instincts that prompt even animals to fight or run. If the negro as a race, intends to remain in this country, and does not combine, organize and put forth endeavors for a better condition of things here or leave it and search for a land more congenial, he is evidently of the lowest type of human existence, and slavery would be a more befitting sphere for the exercise of his dwarfed and servile powers than freedom. When colored people were forced into "Jim-Crow cars" and deprived of any right, which the whites enjoyed in the days of slavery, they were charged half fare. Now they have to pay for first-class fare, and in thousands of instances are compelled to accept half accommodations, but it is needless to enter into further detail, for the same principle or unprinciple runs throughout the entire series.

Therefore, I have compiled and published these documents upon the same for the information of my race everywhere, and their friends, that they may see their odious and direful surroundings, and ask themselves whether they can submit to them or not.

H. M. TURNER.

Atlanta, Ga., November 15, 1893.

Turner’s complete publication can be found at https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/turnerbd/turner.html

The son in A Seat at the Table learned to read at the Beach Institute, and he represents enslaved peoples’ long struggle for literacy. While the Beach Institute was the first official school for African Americans in Savannah, the city was known for its “secret schools” where courageous teachers defied the law and taught small groups of enslaved children in their homes. Susie King Taylor learned to read in these schools. During the Civil War she married an officer in the 33rd United States Colored Infantry Regiment and taught the soldiers in the regiment to read and write. With the publication of Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers , she became the first and only African American woman to write a memoir of her Civil War experiences.

From Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers (pp 5-7)

II

MY CHILDHOOD

I WAS born under the slave law in Georgia, in 1848, and was brought up by my grandmother in Savannah. There were three of us with her, my younger sister and brother. My brother and I being the two eldest, we were sent to a friend of my grandmother, Mrs. Woodhouse, a widow, to learn to read and write. She was a free woman and lived on Bay Lane, between Habersham and Price streets, about half a mile from my house. We went every day about nine o'clock, with our books wrapped in paper to prevent the police or white persons from seeing them. We went in, one at a time, through the gate, into the yard to the L kitchen, which was the schoolroom. She had twenty-five or thirty children whom she taught, assisted by her daughter, Mary Jane. The neighbors would see us going in sometimes, but they supposed we were there learning trades, as it was the custom to give children a trade of some kind. After school we left the same way we entered, one by one, when we would go to a square, about a block from the school, and wait for each other. We would gather laurel leaves and pop them on our hands, on our way home. I remained at her school for two years or more, when I was sent to a Mrs. Mary Beasley, where I continued until May, 1860, when she told my grandmother she had taught me all she knew, and grandmother had better get some one else who could teach me more, so I stopped my studies for a while.

I had a white playmate about this time, named Katie O'Connor, who lived on the next corner of the street from my house, and who attended a convent. One day she told me, if I would promise not to tell her father, she would give me some lessons. On my promise not to do so, and getting her mother's consent, she gave me lessons about four months, every evening. At the end of this time she was put into the convent permanently, and I have never seen her since.

A month after this, James Blouis, our landlord's son, was attending the High School, and was very fond of grandmother, so she asked him to give me a few lessons, which he did until the middle of 1861, when the Savannah Volunteer Guards, to which he and his brother belonged, were ordered to the front under General Barton. In the first battle of Manassas, his brother Eugene was killed, and James deserted over to the Union side, and at the close of the war went to Washington, D. C., where he has since resided. I often wrote passes for my grandmother, for all colored persons, free or slaves, were compelled to have a pass; free colored people having a guardian in place of a master. These passes were good until 10 or 10.30 P. M. for one night or every night for one month. The pass read as follows:--

SAVANNAH, GA., March 1st, 1860.

Pass the bearer--from 9 to 10.30. P. M.

VALENTINE GREST.

Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/taylorsu/taylorsu.html

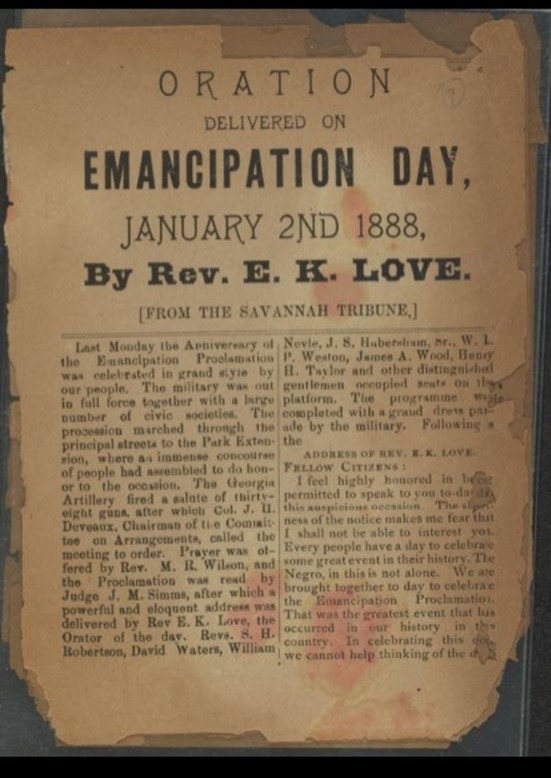

During the early years of Reconstruction African Americans were eager to publish their own newspapers. On February 15, 1868, the Reverend James M. Simms, who was also an elected member of the Georgia Legislature, began publication of Savannah’s first Black newspaper, the Freemen’s Standard. That newspaper was short-lived, but in 1875 Savannah native John H. Deveaux established the Colored Tribune with the stated purpose in his first issue of defending "the rights of the colored people, and their elevation to the highest plane of citizenship.” In 1876 Deveaux changed the name of the paper to the Savannah Tribune, and it is still published under that name today.

Image 1 of Oration delivered on Emancipation Day, January 2nd 1888, published in the Savannah Tribune. Library of Congress - LCCN Permalink https://lccn.loc.gov/91898263